Just a short post today, since Nancy and I are trying to get things in order to go to Colorado on Tuesday, but I've been musing about applying Tournier's person/persona model to God. Please note that, at least at this stage, I'm trying to stay within a classically Christian, trinitarian framework. Perhaps I'll apply this outside that framework, but, honestly, any talk of the divinity being "person" and its extension into persona seems irreducibly Christian.

First question: when we say God is three persons, are we actually saying God is three personas? To stay within a Chalcedonian trinitarian formulation (God is one in essence but three in persons) seems to prohibit dividing God's essence into three persons, so I tend to think of the persons as personas: God had three distinct personas in God's interaction with Israel first and then the rest of humanity. The persona of God the Creator, then, gets recorded differently in scripture: in Genesis, the personal creator; in Exodus, the avenging fire and monarch; etc.

God the Son becomes more complicated, since in good Christian confession God became fleshly person just like you and me. However, even in that situation Jesus would still have a persona, so that one could view the gospels as narratives about Jesus' different personas, i.e. how people engage and interact with Christ. So the incarnation is not a barrier to the whole person/persona thing.

God the Spirit is the least complicated of all, it seems to me, since the scriptures and our own confessions/traditions concern most of all humanity's interactions with the Spirit, i.e. humanity has experienced and will continue to experience the Spirit way more often than the other two personas (the Creator is away, the Son is with the Creator wherever that is, the Spirit, when it wills, blows here and there). So sometimes the Spirit has the persona of teacher, sometimes that of comforter, etc.

Following this model seems to imply two fundamental results. First, the essence of God is unknowable by us, only the personas are knowable (whether historically/scripturally/persently). That means our knowledge/experience of God is always mediated through our own personas, which are developed and interact relationally with God's own personas. Going the other way, God's own personas are developed historically and relationally, too, and undoubtedly will vary based on those with whom God is interacting. This raises all kinds of questions, from the immediacy of revelation in an individual to the question of whether God changes at all. This is actually another way of saying that God's personas and ours are mediated not just individually, but corporately through ethoi: in fact, given that even two personas will be bounded by at least one ethos, God's personas are mostly developed in relationship with group ethoi rather than individual personas. Which is yet another way of saying that God's personas are essentially social. Are there ways of speaking together and constructing narratives (which may not involve conversation as such) that testify truly to God's presence? How do we identify them?

Second, I'm not talking metaphysics here, but narrative. Though I'm certainly willing and hoping to leave open the possibility that God will reveal Godself unmediated by personas to an individual or group, all we have to work with are narratives enmeshed (or enfleshed) in personas and ethoi. In fact, narrative, it seems to me right now, seems exclusively located in persona, perhaps, but most probably in ethos/oi. Again, being Calvinist I'm certainly not attempting to limit God's sovereignty, but arguing that, extending Plaskow's argument in Standing Again at Sinai, the only thing we have to go on are narratives, even instantaneous ones, about God's interaction with us and our relationship with God.

Regarding the question of how to determine whether God's Spirit is present, I guess I'm moving more toward analysis of narratives advocating for the Spirit's presence, even in the case where I'm one of those experiencing something (or someone) that may in fact be the Spirit. The "still, small voice" may indeed speak within a person, but that speaking, it seems to me, must be communicated (whether verbally or actionally), and that takes us immediately to narratives. But also in terms of group experience: persons collectively (as on our recent pilgrimage) experience something that they suspect is divine, so they must talk about it, engaging all the messiness of personas and ethos. How in constructing our narrative can we be assured that what we're experiencing is actually Spirit rather than spirit?

A final note of caution: post-modernism loves narratives and their analysis. We've been post-modern for a century now (in scientific terms, following Luckman), so perhaps we've accepted post-modern tenets uncritically. Yet Kipling, writing during the changeover from modern to post-modern (1895), offered a critique that may still need answers: narratives may be dead wrong according to a non-narrative referent. The Bandar-log in The Jungle Book were fond of saying, "We all say so, and so it must be true," when, at least according to the omniscience of Kipling's narrative, what they said was entirely false. Sadly, in constructing our own narratives we are not so lucky to have such a referent, according to post-modernism (which many reject, by the way). Thank you for reading.

Saturday, July 31, 2010

Friday, July 30, 2010

Trialectic: Prolegomenon

I derive "trialectic" from "dialectic" to denote a three-way conversation between individual (or better yet, "person"), group and God. A trialectic is a conversation - a negotiation, debate, concession, conformation, assent - in which a determinative narrative is negotiated, in that the parties are actively constructing a narrative of meaning that in some ways determine group- and self-identity, goals, purposes, etc. As a conversation that results in a narrative, by looking back (I find it challenging to look presently at these conversations without removing myself from them) we can read these narratives as we would any other. Scripture is a record, in a real sense, of an historic trialectic between person and group and God, though it gets sticky to assign referents to these terms: in reading Scripture, does "person" refer to the historical author, the historical reader/hearer, the contemporary hearer/reader, the implied author, etc. Same for "group" and, even, "God." Please note these referents are not exclusive: indeed, one may open one's reading of scripture dramatically by assuming each of these referents and following where your assumptions lead.

Let's begin with "person." Following Tournier (The Meaning of Persons) I see a person as essentially dyadic instead of monadic. "Dyadic" means a person's selfhood is constructed essentially in relationship with others, "monadic" means a person's selfhood is essentially constructed within a person apart from relationships with others. This are gross definitions, for sure. In biblical times (and still in the Mediterranean today), however, a person's identity was primarily dyadic, with one's family/kin group being existentially before oneself: one was a member of a group first, then an individual second. Indeed, much of the talk of sinfulness in the scriptures derives from placing oneself before one's group.

Yet we cannot escape the fact that we are persons, with interior identities that persist regardless of our primary and secondary groups. Tournier therefore distinguishes between "person" and "persona" - the former denoting our essential interiority, the latter an exteriority in negotiation (or dialogue) with our groups. An enduring human characteristic - becoming painfully apparent in adolescence but persisting throughout our adult lives - is to try and reconcile how one understands one's person with how one's group understands one's persona(s). "You don't know me at all!" is a common protest in this regard. This protest should not be seen as a monadic cry for clarity; rather, it's a further step in a dyadic dialogue of identity. "You don't know me at all, and the way you know me shapes who I am, so let's discuss" is the extension of this protest. So I tend to see a person as dyadically engaged in a persistent conversation about and redefinition of that person's group persona within a specific group. Please note, dyadism implies that it takes just two to make a group: pair-bonds (spouses, partners, mates) are the classic example. But please note also: "person" seems to me to be withdrawn one step from the dynamic I'm trying to discuss, so perhaps I should clarify and define this trialectic as that between persona, group and God.

Turning to groups, groups are composed of persons, always. Groups range from the ad hoc to the historical: in the former, a group may exist momentarily for a very simple purpose. Consider this photo: one of our Israel pilgrimage group, Michiel, happened to be near a small, apparently related group of tourists at the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. For some reason, they invited him to join them in a photo. So Michiel, whom I found to have such an open and warm persona, stepped right into frame and wrapped his arm around the nearest stranger. And they formed a group, right then and there, for about 90 seconds. "Open" and "warm" are characteristics of Michiel's persona in my experience, but surely stem from his person. However, as characteristics of his persona in this instance (and they could well be characteristics of a person and not be characteristics of her or his personas), his open warmness was welcomed and affirmed by this small tour group, making him, for the moment, one of theirs and they some of his. In human ethological terms, the open-torsoed arm hug is a classic marker of non-hostility and, actually, malleability: Michiel and the tourists understood the parameters of this photo opportunity - warmth, openness and togetherness for this brief moment (though note the man Michiel hugs is looking down and away, a distancing move) - and were willing to cooperate, hence, were malleable.

So Michiel, whom I found to have such an open and warm persona, stepped right into frame and wrapped his arm around the nearest stranger. And they formed a group, right then and there, for about 90 seconds. "Open" and "warm" are characteristics of Michiel's persona in my experience, but surely stem from his person. However, as characteristics of his persona in this instance (and they could well be characteristics of a person and not be characteristics of her or his personas), his open warmness was welcomed and affirmed by this small tour group, making him, for the moment, one of theirs and they some of his. In human ethological terms, the open-torsoed arm hug is a classic marker of non-hostility and, actually, malleability: Michiel and the tourists understood the parameters of this photo opportunity - warmth, openness and togetherness for this brief moment (though note the man Michiel hugs is looking down and away, a distancing move) - and were willing to cooperate, hence, were malleable.

Now, think about this small group of tourists as a subgroup of a much larger group, their individual and collective kin-groups, friends, co-workers, synagogues, etc. They're having this picture taken to take back and show to someone (usually, and surely in this case). So I imagine it fits their own personas in relation to those groups to show the folks back home how warm and welcoming and affirming their trip to Israel was, so much so that they found a "kindred soul" in Michiel, who graciously stepped into the photo with them. Those groups back home represent more historical groups, groups that have persisted for a significant (and you can certainly argue with me about what "significant" signifies) time. Surely we can speculate that this five-person group includes two sets of old-marrieds (perhaps the woman in the center is a widow, or her partner is taking the photo) with extended families back home. Perhaps the two couples are related to each other, too. So we're beginning to get an historical sense of their kinship groups, perhaps children and grandchildren, cousins, but also fellow workers, bridge groups, aerobic groups, etc. Further, if I remember correctly they were all Jewish, which extends our discussion of group to ethnicity, perhaps the most persistent historically of groups (paleo-anthropological definitions transcend the historical, but you could also begin to discuss homo sapiens sapiens here). So depending on how one slices one's pie, these persons are parts of groups that range from the ad hoc (the photo session) to the generational (their marriages) to the ethnic (Jewishness). And be sure that each person has to negotiate her or his persona with each and all of these groups.

And just like the person/persona dilemma, groups have their own membership/ethos dilemma. For a group to persist, it has to welcome new members. On welcoming new members, the group brings to bear aggressive dynamics to ensure that the new members will conform to and support group norms, practices, rules - in short, its ethos. Yet new members bring newness to the group, and some of these members will be found to be more beneficial/effective in group-building and -sustaining processes, perhaps in ways the group did not recognize nor anticipate. Hence, members who become prominent begin to alter the group's ethos, leading to a similar dynamic to the person/persona dilemma: "Who are we?" becomes a characteristic query. "What are we doing together?" another. "Why are we here?" a third. So we can easily visualize an inter-group dialectic about identity and purpose, e.g., ethos. But the concept of being "beneficial" or "effective" actually has an extra-group referent: groups always function in wider economies, and beneficial effects are those that help a group to grow and prosper in light of those external realities. So one can see a group as nested in ever-growing and -intersecting larger groups, with which a group is constantly negotiating its own sense of identity and purpose, again, its ethos. So perhaps we should modify my trialectic further, and speak of persona, ethos (which assumes group) and God, with ethos being the negotiated result of two or more personas.

It's tempting to stop with this fundamental, dyadic dialectic, but since this is a discussion of Spirituality, we have to extend our discussion to the divine and speak about a trialectic of persona, ethos and God. Imagine, if you will, a two-dimensional persona/ethos snapshot of overlapping circles: perhaps the persona circle is entirely contained within the ethos circle, perhaps only slightly overlapping (I will complicate this simple diagram in the future, but for our purposes it's best to keep it simple). Just like in the classic book Flatland, these two circles have permeable boundaries, allowing them to interact, but they are essentially two-dimensional. God, in this diagram, can be characterized by a solid sphere, three dimensional, that intersects these two-dimensional circles. In other words, God is much more complex (deeper, wider, but also fuller) than we and our ethoi are. And I tend to think of the divine irrupting, not necessarily in a sense of penetrating from the outside, but also in a sense of swelling from within. Where God penetrates/swells with the persona/ethos dyad, there you have the persona/ethos/God triad. To read and think about the conversation surrounding that triad - the narrative, always reflective, that seeks to process and make sensible that triadic interaction - is what I mean when I speak of a "trialectic."

Now, you may protest that I've moved my discussion from hard, empirical realities like person and group to "softer" realities like persona and ethos. You would be right. Because what I'm interested in is not investigating biology or anthropology but in reading narratives. And narratives grow not out of an analysis of biology and anthropology, but out of the vital interaction between personas and ethoi. In narratives, persons and groups are mediated through their respective personas and ethoi to such an extent that the former are irretrievable: all we have to go on, in reading scripture or in making sense of our relationships, are narratives that derive from our personas' interactions with different ethoi. In my next post I will begin to discuss the differences at the persona and ethos levels between Spirit and spirit. Hopefully, we'll be able to see ways to distinguish, associate and combine the two that helps us make sense of this trialectic in terms of applying it usefully to our lives. Throughout this elaborate post has run an essential (for me) question: how do we know when God is present? And part of that knowing, a crucial part in my humble opinion, is how we distinguish the Spirit from the spirits. Or to be more precise, what are the narrative cues - both presently and historically - the we can read accurately or faithfully to know God's presence. Thank you for reading.

Let's begin with "person." Following Tournier (The Meaning of Persons) I see a person as essentially dyadic instead of monadic. "Dyadic" means a person's selfhood is constructed essentially in relationship with others, "monadic" means a person's selfhood is essentially constructed within a person apart from relationships with others. This are gross definitions, for sure. In biblical times (and still in the Mediterranean today), however, a person's identity was primarily dyadic, with one's family/kin group being existentially before oneself: one was a member of a group first, then an individual second. Indeed, much of the talk of sinfulness in the scriptures derives from placing oneself before one's group.

Yet we cannot escape the fact that we are persons, with interior identities that persist regardless of our primary and secondary groups. Tournier therefore distinguishes between "person" and "persona" - the former denoting our essential interiority, the latter an exteriority in negotiation (or dialogue) with our groups. An enduring human characteristic - becoming painfully apparent in adolescence but persisting throughout our adult lives - is to try and reconcile how one understands one's person with how one's group understands one's persona(s). "You don't know me at all!" is a common protest in this regard. This protest should not be seen as a monadic cry for clarity; rather, it's a further step in a dyadic dialogue of identity. "You don't know me at all, and the way you know me shapes who I am, so let's discuss" is the extension of this protest. So I tend to see a person as dyadically engaged in a persistent conversation about and redefinition of that person's group persona within a specific group. Please note, dyadism implies that it takes just two to make a group: pair-bonds (spouses, partners, mates) are the classic example. But please note also: "person" seems to me to be withdrawn one step from the dynamic I'm trying to discuss, so perhaps I should clarify and define this trialectic as that between persona, group and God.

Turning to groups, groups are composed of persons, always. Groups range from the ad hoc to the historical: in the former, a group may exist momentarily for a very simple purpose. Consider this photo: one of our Israel pilgrimage group, Michiel, happened to be near a small, apparently related group of tourists at the Shrine of the Book in Jerusalem. For some reason, they invited him to join them in a photo.

So Michiel, whom I found to have such an open and warm persona, stepped right into frame and wrapped his arm around the nearest stranger. And they formed a group, right then and there, for about 90 seconds. "Open" and "warm" are characteristics of Michiel's persona in my experience, but surely stem from his person. However, as characteristics of his persona in this instance (and they could well be characteristics of a person and not be characteristics of her or his personas), his open warmness was welcomed and affirmed by this small tour group, making him, for the moment, one of theirs and they some of his. In human ethological terms, the open-torsoed arm hug is a classic marker of non-hostility and, actually, malleability: Michiel and the tourists understood the parameters of this photo opportunity - warmth, openness and togetherness for this brief moment (though note the man Michiel hugs is looking down and away, a distancing move) - and were willing to cooperate, hence, were malleable.

So Michiel, whom I found to have such an open and warm persona, stepped right into frame and wrapped his arm around the nearest stranger. And they formed a group, right then and there, for about 90 seconds. "Open" and "warm" are characteristics of Michiel's persona in my experience, but surely stem from his person. However, as characteristics of his persona in this instance (and they could well be characteristics of a person and not be characteristics of her or his personas), his open warmness was welcomed and affirmed by this small tour group, making him, for the moment, one of theirs and they some of his. In human ethological terms, the open-torsoed arm hug is a classic marker of non-hostility and, actually, malleability: Michiel and the tourists understood the parameters of this photo opportunity - warmth, openness and togetherness for this brief moment (though note the man Michiel hugs is looking down and away, a distancing move) - and were willing to cooperate, hence, were malleable.Now, think about this small group of tourists as a subgroup of a much larger group, their individual and collective kin-groups, friends, co-workers, synagogues, etc. They're having this picture taken to take back and show to someone (usually, and surely in this case). So I imagine it fits their own personas in relation to those groups to show the folks back home how warm and welcoming and affirming their trip to Israel was, so much so that they found a "kindred soul" in Michiel, who graciously stepped into the photo with them. Those groups back home represent more historical groups, groups that have persisted for a significant (and you can certainly argue with me about what "significant" signifies) time. Surely we can speculate that this five-person group includes two sets of old-marrieds (perhaps the woman in the center is a widow, or her partner is taking the photo) with extended families back home. Perhaps the two couples are related to each other, too. So we're beginning to get an historical sense of their kinship groups, perhaps children and grandchildren, cousins, but also fellow workers, bridge groups, aerobic groups, etc. Further, if I remember correctly they were all Jewish, which extends our discussion of group to ethnicity, perhaps the most persistent historically of groups (paleo-anthropological definitions transcend the historical, but you could also begin to discuss homo sapiens sapiens here). So depending on how one slices one's pie, these persons are parts of groups that range from the ad hoc (the photo session) to the generational (their marriages) to the ethnic (Jewishness). And be sure that each person has to negotiate her or his persona with each and all of these groups.

And just like the person/persona dilemma, groups have their own membership/ethos dilemma. For a group to persist, it has to welcome new members. On welcoming new members, the group brings to bear aggressive dynamics to ensure that the new members will conform to and support group norms, practices, rules - in short, its ethos. Yet new members bring newness to the group, and some of these members will be found to be more beneficial/effective in group-building and -sustaining processes, perhaps in ways the group did not recognize nor anticipate. Hence, members who become prominent begin to alter the group's ethos, leading to a similar dynamic to the person/persona dilemma: "Who are we?" becomes a characteristic query. "What are we doing together?" another. "Why are we here?" a third. So we can easily visualize an inter-group dialectic about identity and purpose, e.g., ethos. But the concept of being "beneficial" or "effective" actually has an extra-group referent: groups always function in wider economies, and beneficial effects are those that help a group to grow and prosper in light of those external realities. So one can see a group as nested in ever-growing and -intersecting larger groups, with which a group is constantly negotiating its own sense of identity and purpose, again, its ethos. So perhaps we should modify my trialectic further, and speak of persona, ethos (which assumes group) and God, with ethos being the negotiated result of two or more personas.

It's tempting to stop with this fundamental, dyadic dialectic, but since this is a discussion of Spirituality, we have to extend our discussion to the divine and speak about a trialectic of persona, ethos and God. Imagine, if you will, a two-dimensional persona/ethos snapshot of overlapping circles: perhaps the persona circle is entirely contained within the ethos circle, perhaps only slightly overlapping (I will complicate this simple diagram in the future, but for our purposes it's best to keep it simple). Just like in the classic book Flatland, these two circles have permeable boundaries, allowing them to interact, but they are essentially two-dimensional. God, in this diagram, can be characterized by a solid sphere, three dimensional, that intersects these two-dimensional circles. In other words, God is much more complex (deeper, wider, but also fuller) than we and our ethoi are. And I tend to think of the divine irrupting, not necessarily in a sense of penetrating from the outside, but also in a sense of swelling from within. Where God penetrates/swells with the persona/ethos dyad, there you have the persona/ethos/God triad. To read and think about the conversation surrounding that triad - the narrative, always reflective, that seeks to process and make sensible that triadic interaction - is what I mean when I speak of a "trialectic."

Now, you may protest that I've moved my discussion from hard, empirical realities like person and group to "softer" realities like persona and ethos. You would be right. Because what I'm interested in is not investigating biology or anthropology but in reading narratives. And narratives grow not out of an analysis of biology and anthropology, but out of the vital interaction between personas and ethoi. In narratives, persons and groups are mediated through their respective personas and ethoi to such an extent that the former are irretrievable: all we have to go on, in reading scripture or in making sense of our relationships, are narratives that derive from our personas' interactions with different ethoi. In my next post I will begin to discuss the differences at the persona and ethos levels between Spirit and spirit. Hopefully, we'll be able to see ways to distinguish, associate and combine the two that helps us make sense of this trialectic in terms of applying it usefully to our lives. Throughout this elaborate post has run an essential (for me) question: how do we know when God is present? And part of that knowing, a crucial part in my humble opinion, is how we distinguish the Spirit from the spirits. Or to be more precise, what are the narrative cues - both presently and historically - the we can read accurately or faithfully to know God's presence. Thank you for reading.

Thursday, July 29, 2010

Water

Tying my musings on Spirit/spirit to my trip to Israel, I think some comments on water in Israel are in order. The tie between Spirit/spirit and water is occasionally made in the scriptures, where a text will speak of the Spirit's being "poured out" in language typically used for water (Hebrew Bible) or of the baptism (or "washing") by the Holy Spirit (Christian New Testament). I'm interested in the politics of water in Israel modern and ancient, following up on my earlier posts about walls. Should the kind reader protest about politicizing the Spirit/spirit, I should note the more fundamental meaning of "politics," "politic" and "polity" as having to do with interactions between and among groups of people (and "group" being one party of the soon-to-be-discussed trialectic between individual, group and God) and the feminist caution that politics and power pervade all our narratives, even those about Spirit/spirit. Further, "spirit" - as in a "spirited" person or the "spirit" at a pep rally, may be seen as one expression of power - aggressivity or vitality.

Here's a view of the Sea of Galilee from Mt. Arbel, looking NNE at the NW shore of the Sea of Galilee. In this one picture you can see where Jesus, according to the Gospels, spent most of his ministry. The Galilee, according to Claudia our guide, is "water rich," owing to the immense quantity of fresh water in the Sea of Galilee. This is in contrast to the parts of Israel that are "water poor" - practically everywhere else. Indeed, Israel pipes water from the Sea of Galilee even as far as the Negeb. Israel also has dammed the Jordan River at its outlet from the Sea of Galilee, first to secure more water for the rest of Israel through its pipe system but, second, to keep Jordan from benefiting from the water along the formally eastern shore of the Jordan down to the Dead Sea. Politics, again. But for my purposes, please note how easy it is to get a drink of water in the Galilee: go to the shore and dip some out (in modern times, treat before drink).

Here's a view of the Sea of Galilee from Mt. Arbel, looking NNE at the NW shore of the Sea of Galilee. In this one picture you can see where Jesus, according to the Gospels, spent most of his ministry. The Galilee, according to Claudia our guide, is "water rich," owing to the immense quantity of fresh water in the Sea of Galilee. This is in contrast to the parts of Israel that are "water poor" - practically everywhere else. Indeed, Israel pipes water from the Sea of Galilee even as far as the Negeb. Israel also has dammed the Jordan River at its outlet from the Sea of Galilee, first to secure more water for the rest of Israel through its pipe system but, second, to keep Jordan from benefiting from the water along the formally eastern shore of the Jordan down to the Dead Sea. Politics, again. But for my purposes, please note how easy it is to get a drink of water in the Galilee: go to the shore and dip some out (in modern times, treat before drink).

Nonetheless, fortresses from biblical times needed secure sources of water apart from the Sea of Galilee. Though in peacetime (rare in the Middle East even then) one can easily get water from the Sea of Galilee, during siege that was impossible. Instead, walled cities - and the walls were there primarily for the government and military, the peasantry or commoners lived outside the city walls - needed dependable water sources within the city walls. Here's a picture from Hazor at the north end of the Sea of Galilee. The view is from inside the water tunnel carved through the bedrock to a spring that was formerly outside the city walls. You can see what an undertaking this was for the people of Hazor (probably not the governors or soldiers, mind you). With the tunnel constructed and the exterior access to the spring walled up and hidden, the city could be assured of fresh water in the event of a siege. Please note, however, that to gain access to this life-preserving water during siege, one had to move within the city walls, through well-protected gates, presumably showing sufficient identification and allegiance. That means politics, a crossing behind walls that impels one to confirm her or his loyalty to and identification with a group.

The view is from inside the water tunnel carved through the bedrock to a spring that was formerly outside the city walls. You can see what an undertaking this was for the people of Hazor (probably not the governors or soldiers, mind you). With the tunnel constructed and the exterior access to the spring walled up and hidden, the city could be assured of fresh water in the event of a siege. Please note, however, that to gain access to this life-preserving water during siege, one had to move within the city walls, through well-protected gates, presumably showing sufficient identification and allegiance. That means politics, a crossing behind walls that impels one to confirm her or his loyalty to and identification with a group.

Tunneling to water happened at other fortified cities where the main spring was outside the city walls. Here's a picture of the descent into Megiddo's formidable water tunnel, itself 215 feet long, famously fictionalized in Michener's "The Source." Megiddo sits at one end of the Jezreel valley, the principal highway between the kingdoms of Egypt and Mesopotamia and the locus for many historic battles. Like at Hazor, during siege the folks outside the walls had to move inside the walls; the tunnel assured all would have fresh, "living" water during the siege. Again, to benefit from this life-giving water, presumably one had to pass within the city walls, assuring the guards one was in fact in allegiance with the rulers within. Now, I don't mean to imply that there was anything despotic about this: I assume those moving within would have felt quite comforted by the strong walls and soldiers guarding the city during siege. But I would be mistaken not to recognize the politics involved.

Like at Hazor, during siege the folks outside the walls had to move inside the walls; the tunnel assured all would have fresh, "living" water during the siege. Again, to benefit from this life-giving water, presumably one had to pass within the city walls, assuring the guards one was in fact in allegiance with the rulers within. Now, I don't mean to imply that there was anything despotic about this: I assume those moving within would have felt quite comforted by the strong walls and soldiers guarding the city during siege. But I would be mistaken not to recognize the politics involved.

When we come to Jerusalem in Jesus' time, the picture is a bit more complex. At the very least, the guards for the city were Herodians - thralls to Roman power, seen by some as traitors to Israel. The primary sources of water within the city walls were the pools of Siloam and Bethesda, the latter reached underneath the city of Salem in David's time by Hezekiah's tunnel, itself a marvel of engineering. But unlike Hazor and Megiddo, one living outside the city walls in Jesus' time had to pass through a gate guarded by supposed enemies, to give at least tacit allegiance to a foreign ruling power. Jesus' words, then, should not be stripped of their political content when he cries in John 7, "If anyone is thirsty let him (or her) come to me and drink: the one who believes in me, just as the scriptures say, 'Out of his (or her) heart rivers of living water will flow.'" It seems to me Jesus is offering his believers not just the Spirit/spirit in dramatic quantity, but the freedom of individual spirituality unhampered by political or group loyalties.

And to further solidify the connection between Spirit/spirit and water, John goes on to add, "He said this about the Spirit/spirit which those who believed in him were going to receive, for there was not yet a Spirit/spirit because Jesus had not yet been glorified." Interesting to note that whereas the Bible often speaks of the Spirit/spirit being poured out on people, here Jesus is speaking of the Spirit/spirit being poured out from people. Yet even though one may read Jesus' claim as bypassing groupness or politics, the thirst-quenching Spirit/spirit is not just for the benefit of the individual; rather, the individual becomes the source of life for those around her. Again, Jesus' statement finds its full force in Jerusalem rather than Galilee, since in the Galilee many sources of living water were available outside any walls.

We in the United States live in a "water-rich" country (even though we shamefully waste good, clean and energy-expensive drinking water by flushing our toilets with it), so it's hard for us to catch the full import of either Jesus' words or of water behind walls. The closest we come is periods of water rationing, but usually we're asked to curtail our private use instead of reiterating our allegiance to our government in the process. So it's equally hard for us to get a grip on the trialectic between individual, group and God in the scriptures. I hope this brief post has made some of those latter issues clearer. Of course, it's a separate question whether our musings on the Spirit/spirit must be constrained by scripture. Yet I find scripture not only to be theologically revelatory, but (in a more secular understanding) an ancient text with as great wisdom about the human condition as any other ancient, revered text. And being Christian, scripture does form the bedrock of my own theological constructions, though the edifices I build on that bedrock perhaps would seem strange to its founders. Thank you for reading.

Here's a view of the Sea of Galilee from Mt. Arbel, looking NNE at the NW shore of the Sea of Galilee. In this one picture you can see where Jesus, according to the Gospels, spent most of his ministry. The Galilee, according to Claudia our guide, is "water rich," owing to the immense quantity of fresh water in the Sea of Galilee. This is in contrast to the parts of Israel that are "water poor" - practically everywhere else. Indeed, Israel pipes water from the Sea of Galilee even as far as the Negeb. Israel also has dammed the Jordan River at its outlet from the Sea of Galilee, first to secure more water for the rest of Israel through its pipe system but, second, to keep Jordan from benefiting from the water along the formally eastern shore of the Jordan down to the Dead Sea. Politics, again. But for my purposes, please note how easy it is to get a drink of water in the Galilee: go to the shore and dip some out (in modern times, treat before drink).

Here's a view of the Sea of Galilee from Mt. Arbel, looking NNE at the NW shore of the Sea of Galilee. In this one picture you can see where Jesus, according to the Gospels, spent most of his ministry. The Galilee, according to Claudia our guide, is "water rich," owing to the immense quantity of fresh water in the Sea of Galilee. This is in contrast to the parts of Israel that are "water poor" - practically everywhere else. Indeed, Israel pipes water from the Sea of Galilee even as far as the Negeb. Israel also has dammed the Jordan River at its outlet from the Sea of Galilee, first to secure more water for the rest of Israel through its pipe system but, second, to keep Jordan from benefiting from the water along the formally eastern shore of the Jordan down to the Dead Sea. Politics, again. But for my purposes, please note how easy it is to get a drink of water in the Galilee: go to the shore and dip some out (in modern times, treat before drink).Nonetheless, fortresses from biblical times needed secure sources of water apart from the Sea of Galilee. Though in peacetime (rare in the Middle East even then) one can easily get water from the Sea of Galilee, during siege that was impossible. Instead, walled cities - and the walls were there primarily for the government and military, the peasantry or commoners lived outside the city walls - needed dependable water sources within the city walls. Here's a picture from Hazor at the north end of the Sea of Galilee.

The view is from inside the water tunnel carved through the bedrock to a spring that was formerly outside the city walls. You can see what an undertaking this was for the people of Hazor (probably not the governors or soldiers, mind you). With the tunnel constructed and the exterior access to the spring walled up and hidden, the city could be assured of fresh water in the event of a siege. Please note, however, that to gain access to this life-preserving water during siege, one had to move within the city walls, through well-protected gates, presumably showing sufficient identification and allegiance. That means politics, a crossing behind walls that impels one to confirm her or his loyalty to and identification with a group.

The view is from inside the water tunnel carved through the bedrock to a spring that was formerly outside the city walls. You can see what an undertaking this was for the people of Hazor (probably not the governors or soldiers, mind you). With the tunnel constructed and the exterior access to the spring walled up and hidden, the city could be assured of fresh water in the event of a siege. Please note, however, that to gain access to this life-preserving water during siege, one had to move within the city walls, through well-protected gates, presumably showing sufficient identification and allegiance. That means politics, a crossing behind walls that impels one to confirm her or his loyalty to and identification with a group.Tunneling to water happened at other fortified cities where the main spring was outside the city walls. Here's a picture of the descent into Megiddo's formidable water tunnel, itself 215 feet long, famously fictionalized in Michener's "The Source." Megiddo sits at one end of the Jezreel valley, the principal highway between the kingdoms of Egypt and Mesopotamia and the locus for many historic battles.

Like at Hazor, during siege the folks outside the walls had to move inside the walls; the tunnel assured all would have fresh, "living" water during the siege. Again, to benefit from this life-giving water, presumably one had to pass within the city walls, assuring the guards one was in fact in allegiance with the rulers within. Now, I don't mean to imply that there was anything despotic about this: I assume those moving within would have felt quite comforted by the strong walls and soldiers guarding the city during siege. But I would be mistaken not to recognize the politics involved.

Like at Hazor, during siege the folks outside the walls had to move inside the walls; the tunnel assured all would have fresh, "living" water during the siege. Again, to benefit from this life-giving water, presumably one had to pass within the city walls, assuring the guards one was in fact in allegiance with the rulers within. Now, I don't mean to imply that there was anything despotic about this: I assume those moving within would have felt quite comforted by the strong walls and soldiers guarding the city during siege. But I would be mistaken not to recognize the politics involved.When we come to Jerusalem in Jesus' time, the picture is a bit more complex. At the very least, the guards for the city were Herodians - thralls to Roman power, seen by some as traitors to Israel. The primary sources of water within the city walls were the pools of Siloam and Bethesda, the latter reached underneath the city of Salem in David's time by Hezekiah's tunnel, itself a marvel of engineering. But unlike Hazor and Megiddo, one living outside the city walls in Jesus' time had to pass through a gate guarded by supposed enemies, to give at least tacit allegiance to a foreign ruling power. Jesus' words, then, should not be stripped of their political content when he cries in John 7, "If anyone is thirsty let him (or her) come to me and drink: the one who believes in me, just as the scriptures say, 'Out of his (or her) heart rivers of living water will flow.'" It seems to me Jesus is offering his believers not just the Spirit/spirit in dramatic quantity, but the freedom of individual spirituality unhampered by political or group loyalties.

And to further solidify the connection between Spirit/spirit and water, John goes on to add, "He said this about the Spirit/spirit which those who believed in him were going to receive, for there was not yet a Spirit/spirit because Jesus had not yet been glorified." Interesting to note that whereas the Bible often speaks of the Spirit/spirit being poured out on people, here Jesus is speaking of the Spirit/spirit being poured out from people. Yet even though one may read Jesus' claim as bypassing groupness or politics, the thirst-quenching Spirit/spirit is not just for the benefit of the individual; rather, the individual becomes the source of life for those around her. Again, Jesus' statement finds its full force in Jerusalem rather than Galilee, since in the Galilee many sources of living water were available outside any walls.

We in the United States live in a "water-rich" country (even though we shamefully waste good, clean and energy-expensive drinking water by flushing our toilets with it), so it's hard for us to catch the full import of either Jesus' words or of water behind walls. The closest we come is periods of water rationing, but usually we're asked to curtail our private use instead of reiterating our allegiance to our government in the process. So it's equally hard for us to get a grip on the trialectic between individual, group and God in the scriptures. I hope this brief post has made some of those latter issues clearer. Of course, it's a separate question whether our musings on the Spirit/spirit must be constrained by scripture. Yet I find scripture not only to be theologically revelatory, but (in a more secular understanding) an ancient text with as great wisdom about the human condition as any other ancient, revered text. And being Christian, scripture does form the bedrock of my own theological constructions, though the edifices I build on that bedrock perhaps would seem strange to its founders. Thank you for reading.

Tuesday, July 27, 2010

Spirit and spirit

Having just returned from a spiritual pilgrimage in Israel, and soon to go with Nancy on another (we'll hike the French way on El Camino de Santiago in September), I thought I'd begin several posts about spirit and Spirit. I encourage your reading carefully these thoughts and responding critically. My writing about spirit/Spirit is a way of sorting out what I think. And I sort things out by reading what I wrote. So I'll be reading, too.

I think we must distinguish between "Spirit" and "spirit," and their derivatives "Spiritual" and "spirited." Spirit's locus is the divine, spirit the human/animal. Though these loci are usually thought of as being ontologically distinct (think of the sacred/profane oppositional pair), one could conceive of them as a polarity (following Tillich) with pure Spirit at one end and pure spirit at another (perhaps the animus/anima in animals). I like Tillich's conception of polarity because of one primary implication: Spirit and spirit overlap, are enmeshed, so that even in the most extreme case of Spirit, some spirit is evident, and in the most extreme case of spirit, some Spirit is evident. So God's animating power pervades even the simplest life; conversely, the simplest life participates in the divine.

But when we speak of God in terms of persons (and I tend to do so, being Christian), this polarity becomes harder to maintain. When we speak of the Spirit as person, we're actually saying the Spirit is bounded in some way, is distinct, and should be distinguished from spirit. When we wish to determine whether we're experiencing Spirit or spirit, how do we distinguish the two, especially if we think of them as enmeshed? In more classical terms, any experience of the divine is necessarily mediated through the mundane: we experience God in our flesh, or in our fleshly communion with one another. So how can we tell if the Spirit is really present?

Turning to Scripture, Paul says we can identify the Spirit's presence or effect by its fruits: "By contrast (with the flesh), the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control." (Gal. 5.22-23a) Yet Paul is writing about "flesh" in terms of a daemonic principality that aggressively counters the divine Spirit, advancing his eschatological argument that the church exists in an end time of supernatural conflict. If I step away from his argument, I can also surely see love, joy, peace, patience, etc. as fruits of the spirit as well as the Spirit. After all, these same attributes have been foundational for human community throughout our long evolution: without them, I doubt we'd be here as humans.

Again, thinking about a continuum between Spirit and spirit, I am not surprised that our best attributes as humans are enmeshed with the effects of God's spirit. But I'm extremely hesitant to argue that even our best attributes are necessarily effects of God's Spirit because of the Spirit's distinctness. I do not want to reduce God's Spirit to something akin to Obi Wan's Force, nor to the sacrilized conception of "life" as something holy. God, even in the third person Spirit, is still Other, Mysterium Tremendum (Otto, of course), whirlwind, all-consuming but not burning fire. And in trying to determine whether an experience is driven by the divinity or by human propensities, the conception of distinctness/personhood seems necessary.

Well, you may say, "Why distinguish? You've been on a spiritual pilgrimage, why wonder whether you experienced human group dynamics or the very presence of God?" Because, given my narrative presuppositions, the argument of that question seems to keep unexamined the narrative about our experience (I'm including my pilgrimage group now), and unexamined narratives are not fully read. Unexamined narratives, conflating Spirit and spirit, have a dastardly history. Now, I'm not imputing anything dastardly to our pilgrimage, participants or leaders. But I hope you see my reservation: without examining the narrative, someone can easily sell us on its being Spiritual instead of spirited. Narratives, certainly my own, always entail rhetoric, an attempt to convince someone of something. And rhetoric is not always benign.

So how to distinguish? In my next post, I'll address this by thinking about a trialectic (advanced from dialectic) between individual, group and God. Thank you for reading.

I think we must distinguish between "Spirit" and "spirit," and their derivatives "Spiritual" and "spirited." Spirit's locus is the divine, spirit the human/animal. Though these loci are usually thought of as being ontologically distinct (think of the sacred/profane oppositional pair), one could conceive of them as a polarity (following Tillich) with pure Spirit at one end and pure spirit at another (perhaps the animus/anima in animals). I like Tillich's conception of polarity because of one primary implication: Spirit and spirit overlap, are enmeshed, so that even in the most extreme case of Spirit, some spirit is evident, and in the most extreme case of spirit, some Spirit is evident. So God's animating power pervades even the simplest life; conversely, the simplest life participates in the divine.

But when we speak of God in terms of persons (and I tend to do so, being Christian), this polarity becomes harder to maintain. When we speak of the Spirit as person, we're actually saying the Spirit is bounded in some way, is distinct, and should be distinguished from spirit. When we wish to determine whether we're experiencing Spirit or spirit, how do we distinguish the two, especially if we think of them as enmeshed? In more classical terms, any experience of the divine is necessarily mediated through the mundane: we experience God in our flesh, or in our fleshly communion with one another. So how can we tell if the Spirit is really present?

Turning to Scripture, Paul says we can identify the Spirit's presence or effect by its fruits: "By contrast (with the flesh), the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, generosity, faithfulness, gentleness, and self-control." (Gal. 5.22-23a) Yet Paul is writing about "flesh" in terms of a daemonic principality that aggressively counters the divine Spirit, advancing his eschatological argument that the church exists in an end time of supernatural conflict. If I step away from his argument, I can also surely see love, joy, peace, patience, etc. as fruits of the spirit as well as the Spirit. After all, these same attributes have been foundational for human community throughout our long evolution: without them, I doubt we'd be here as humans.

Again, thinking about a continuum between Spirit and spirit, I am not surprised that our best attributes as humans are enmeshed with the effects of God's spirit. But I'm extremely hesitant to argue that even our best attributes are necessarily effects of God's Spirit because of the Spirit's distinctness. I do not want to reduce God's Spirit to something akin to Obi Wan's Force, nor to the sacrilized conception of "life" as something holy. God, even in the third person Spirit, is still Other, Mysterium Tremendum (Otto, of course), whirlwind, all-consuming but not burning fire. And in trying to determine whether an experience is driven by the divinity or by human propensities, the conception of distinctness/personhood seems necessary.

Well, you may say, "Why distinguish? You've been on a spiritual pilgrimage, why wonder whether you experienced human group dynamics or the very presence of God?" Because, given my narrative presuppositions, the argument of that question seems to keep unexamined the narrative about our experience (I'm including my pilgrimage group now), and unexamined narratives are not fully read. Unexamined narratives, conflating Spirit and spirit, have a dastardly history. Now, I'm not imputing anything dastardly to our pilgrimage, participants or leaders. But I hope you see my reservation: without examining the narrative, someone can easily sell us on its being Spiritual instead of spirited. Narratives, certainly my own, always entail rhetoric, an attempt to convince someone of something. And rhetoric is not always benign.

So how to distinguish? In my next post, I'll address this by thinking about a trialectic (advanced from dialectic) between individual, group and God. Thank you for reading.

Handbuilt Green

I wrote the article below last winter for our presbytery exec, who promptly left and became the executive presbyter for Greater Atlanta presbytery (Godspeed, Tom), so I'm posting it here for your reading pleasure. Two comments: first, the image here is of our laundry room, not our home, but it shows clearly some of the technologies we use (e.g., strawbales, earthbag foundation, recycled window). Second, I've found that some people think handbuilt homes are "unpatriotic," in that to consume on credit in our country is the primary way we as good citizens keep the economy going. I don't subscribe to that notion at all. Rather, a gradual transition to green/efficient/non-petroleum based economies seems to me to be very patriotic. Anyway, thank you for reading.

I wrote the article below last winter for our presbytery exec, who promptly left and became the executive presbyter for Greater Atlanta presbytery (Godspeed, Tom), so I'm posting it here for your reading pleasure. Two comments: first, the image here is of our laundry room, not our home, but it shows clearly some of the technologies we use (e.g., strawbales, earthbag foundation, recycled window). Second, I've found that some people think handbuilt homes are "unpatriotic," in that to consume on credit in our country is the primary way we as good citizens keep the economy going. I don't subscribe to that notion at all. Rather, a gradual transition to green/efficient/non-petroleum based economies seems to me to be very patriotic. Anyway, thank you for reading.Handbuilt Green Strawbale Home in Alabama

“What if we could build a house for less than $10,000.00,” Nancy and I asked ourselves in 2007. Having adopted Dave Ramsey’s “no debt” financial management, and noticing anxious trends in the housing and financial markets, we realized that if we could build a house for such a low amount and sell our existing house, we would find ourselves debt-free with a good chunk of change in the bank. And once our youngest child, our daughter, graduated from college in 2010, we’d have a rosy net worth with invaluable peace about our financial future. We believed we could accomplish this if we imposed some limits on our lifestyle, particularly if we built a much smaller house that the one we had but also if we limited the cost of operating our planned home.

Well, I’m typing this in our 500 square foot home, which is at a comfortable 72 degrees while being heated by forty cents worth of wood (locally bought at four cents per pound) in our wood stove even though it’s blustery and in the high 30’s outside, we have no debt, our daughter is on track to graduate, we have a nice chunk of change in the bank, and we built our home for $7,500.00 instead of $10,000.00. And the key piece in our financial plan, building an economical house for the cost of a decent used car, we accomplished by building with green technologies.

Well, I’m typing this in our 500 square foot home, which is at a comfortable 72 degrees while being heated by forty cents worth of wood (locally bought at four cents per pound) in our wood stove even though it’s blustery and in the high 30’s outside, we have no debt, our daughter is on track to graduate, we have a nice chunk of change in the bank, and we built our home for $7,500.00 instead of $10,000.00. And the key piece in our financial plan, building an economical house for the cost of a decent used car, we accomplished by building with green technologies.“Green technologies” are products and materials that reduce environmental impacts in their manufacture and save energy in their use. Most people are aware of green technologies due to their increasing visibility in advertising for products ranging from light bulbs to cars to entire buildings. I call green technologies that are manufactured for sale to the building industry “commercial green.” In the construction industry, commercial green technologies tend to add twenty to twenty-five percent to the cost of a building’s construction, so we realized we couldn’t reach our building goal by using commercial green technologies.

However, commercial green technologies are not the only green technologies available. For half a century, what I would call “base communities” in this country have promoted and constructed “handbuilt” homes based on the principal of individual rather than commercial construction. And while we certainly support commercial green technologies in the construction industry (indeed, we use some of these technologies in our home), I’d like to tell you about my and Nancy’s work in “handbuilt green” construction in the building of our home.

We define handbuilt green along three parameters: minimal size and cost of construction, handbuilt from local green materials, and minimal use of utilities in the finished home. Nancy and I planned our home, which we refer to as our “private area,” in conjunction with my brother’s and his wife’s private area, seeking to shrink these homes to their bare essentials. Their private area is approximately 600 square feet, ours is 500 square feet, and we share a laundry building of 100 square feet. So our private area plus half of the laundry room comes to 550 square feet and includes a bedroom, a living room with a wood stove, and a reading/office area in one great room, an outdoor kitchen on our back porch, and our bathroom and shower in the laundry building (our shower is actually outdoors, too).

We define handbuilt green along three parameters: minimal size and cost of construction, handbuilt from local green materials, and minimal use of utilities in the finished home. Nancy and I planned our home, which we refer to as our “private area,” in conjunction with my brother’s and his wife’s private area, seeking to shrink these homes to their bare essentials. Their private area is approximately 600 square feet, ours is 500 square feet, and we share a laundry building of 100 square feet. So our private area plus half of the laundry room comes to 550 square feet and includes a bedroom, a living room with a wood stove, and a reading/office area in one great room, an outdoor kitchen on our back porch, and our bathroom and shower in the laundry building (our shower is actually outdoors, too).Having planned our house to be of minimal size, we sought to build it for the least amount of money possible. Since we live in St. Clair county, the only building code we have is for the septic system, meaning we could do every phase of our construction without hiring licensed subcontractors (which most building codes require) apart from installing the septic tank and field lines. That meant we could avoid labor costs altogether: since Nancy and I have built three homes previously, we were skilled in all aspects of home construction. Yet even without paying labor costs, our target of spending between $10.00 and $20.00 per square foot for our new home seemed unduly optimistic, given the costs of materials.

We beat these material costs by following the second principle – handbuilt from local materials – assiduously. Our home is a modified timber frame construction with strawbale infill walls. The timber frame consists of 4x6 pressure treated posts with a conventional roofing system topped with asphalt shingles. The frame and roof use conventional construction materials, so our savings were not noticeable (apart from labor). However, the rest of the house uses non-conventional construction materials, all produced locally. Our strawbale walls rest on earthbag stem walls resting on a gravel fill foundation.

After hiring a local excavator to dig our foundation trenches ($600.00), we installed a French drain and filled the trenches with gravel from a local supplier. We used the dirt we excavated from the trenches for three purposes: first, we filled sandbags with a moist mixture of this dirt, set them in place and tamped them down straight and level, forming foundation walls. Imagine big, heavy but somewhat floppy bricks stacked with recycled barbed wire between the courses to serve as “mortar.” On these stem walls we stacked our strawbales – small, square bales roughly 14” x 18” x 36” – again just like you’d stack bricks in a brick wall. Second, we mixed our excavated dirt with chopped straw as a binder, forming an earthen plaster base coat for our final two coats of lime plaster. Finally, we screened our excavated dirt and added straw to form an earthen floor in the living and office areas. After finishing the floor using an English recipe of high-content clay soil, a soil we were lucky to find elsewhere on our property, we hardened the floor with boiled linseed oil and finished with three coats of polyurethane.

To address the third parameter – minimal use of utilities – Nancy and I decided to design our home as a passive solar home. Passive solar technologies rely on three factors: southern exposure with lots of south wall windows, a high mass heat storage system, and excellent insulation. In addition, we sought to construct these systems as greenly as possible. The long axis of our home, which encloses the earthen floor, faces due south with forty percent of the wall area comprised of windows. We calculated the roof overhangs to allow the sun to shine on the floor beginning with the autumn equinox and ending with the spring equinox. For high mass heat storage, our earthen floor is approximately five inches thick, tightly compacted and a natural dark brown color to absorb heat from direct sunlight. Realizing that the sun doesn’t always shine in Alabama, Nancy and I purchased a used wood stove and stovepipe for backup heat ($400.00).

To address the third parameter – minimal use of utilities – Nancy and I decided to design our home as a passive solar home. Passive solar technologies rely on three factors: southern exposure with lots of south wall windows, a high mass heat storage system, and excellent insulation. In addition, we sought to construct these systems as greenly as possible. The long axis of our home, which encloses the earthen floor, faces due south with forty percent of the wall area comprised of windows. We calculated the roof overhangs to allow the sun to shine on the floor beginning with the autumn equinox and ending with the spring equinox. For high mass heat storage, our earthen floor is approximately five inches thick, tightly compacted and a natural dark brown color to absorb heat from direct sunlight. Realizing that the sun doesn’t always shine in Alabama, Nancy and I purchased a used wood stove and stovepipe for backup heat ($400.00).Strawbales provide excellent insulation as well as being extremely green. Formerly, wheat farmers would burn off the wheat stalks left over from harvesting. Over the last twenty years, people have been convincing farmers to bale these stalks instead of burning them, offering handbuilders and contractors a building technique first used in this country in the mid- to late-1800’s. In fact, one of the longest-standing strawbale structures in this country is the Burris Mansion in Huntsville, built in the 1930’s. By using this waste product from wheat farming, we took advantage of their local availability (we bought ours out of a field in Cullman), low cost (we paid $3.25 per bale) and, most importantly, their high insulating properties. According to rigorous tests, strawbales stacked and plastered as we have done have an R-value exceeding 40. Consequently, our home functions successfully, deriving most of our heat from the sun.

To reduce our electricity demand further, we opted to forego large appliances, having no air conditioning (we will reverse the passive solar heating process for the summer, using the floor to help cool the house) or tank water heater (our heater is tankless), two of the greatest electricity users in a conventional house. We also use low-wattage fluorescent bulbs throughout the house. In fact, our entire home is on one thirty-amp circuit. In the near future, we will convert our toilet to a grey-water system to help conserve drinking water (with which we flush our toilets in this country) and the energy costs of producing clean water.

I’m certain handbuilt advocates will recognize and applaud most of these construction techniques. We could be greener still, for instance, by using wood scavenged from other construction sites, foregoing the pressure treated posts and the poly on the floor. And conventional home owners usually respond to our construction story by asserting that they would never have to skills and time to construct their home themselves, much less using such non-conventional building materials. Building one’s own home takes gumption above all, and though I believe people have reserves of gumption just waiting to be freed from conventional approaches, I recognize that all of us have limits

I’m certain handbuilt advocates will recognize and applaud most of these construction techniques. We could be greener still, for instance, by using wood scavenged from other construction sites, foregoing the pressure treated posts and the poly on the floor. And conventional home owners usually respond to our construction story by asserting that they would never have to skills and time to construct their home themselves, much less using such non-conventional building materials. Building one’s own home takes gumption above all, and though I believe people have reserves of gumption just waiting to be freed from conventional approaches, I recognize that all of us have limitsBut in conclusion, I’d like to advocate for the limits associated with minimal construction. Nancy and I have found these limits to be, surprisingly, liberating. In our small house, we’ve found we focus on having enough space instead of too much. So we focus on what we need instead of want, of having the right piece of furniture in the right place instead of furnishing an entire room. We’ve found a growing pride in being radical rather than being extravagant, recognizing that our lifestyle places few demands on both our environment and us, since we are liberated from much of the maintenance and expense of larger homes. Finally, our small space has given us a renewed intimacy with each other: since we’re always in the same room with each other, we share time and space much more often than we did in our former home. Further, we share a deep intimacy with our home, not just because of its small size, but because the effects of our hands appear all over it. We’ve found the liberating force of small home construction to be one of the best benefits from building green.

Friday, July 23, 2010

The Wall

As a followup to my fences post, I'd like to read the wall a bit. Here's a typical example of the wall Israel has constructed between the state of Israel and the West Bank, minus the barbed wire along its top. Concrete seems to be Israel's favorite construction material (followed closely by concrete block), so much of the wall is constructed of concrete panels. The wall has both a practical and strategic aim. Practically, the wall separates and controls intercourse between Israel and Palestine, allowing people to pass from one to the other only through military checkpoints. Strategically, the wall is being constructed in such a way as to break transportation and communication routes between sectors of the West Bank. Online you will find various maps that show the current extent of the wall system and its planned additions. The wall does remind me of the walls around the Old City, built by an Islamic nobleman in the sixteenth century. The Old City walls have fortified gates and served defensive purposes. To be charitable to the Israelis, the wall serves defensive purposes as well.

As a followup to my fences post, I'd like to read the wall a bit. Here's a typical example of the wall Israel has constructed between the state of Israel and the West Bank, minus the barbed wire along its top. Concrete seems to be Israel's favorite construction material (followed closely by concrete block), so much of the wall is constructed of concrete panels. The wall has both a practical and strategic aim. Practically, the wall separates and controls intercourse between Israel and Palestine, allowing people to pass from one to the other only through military checkpoints. Strategically, the wall is being constructed in such a way as to break transportation and communication routes between sectors of the West Bank. Online you will find various maps that show the current extent of the wall system and its planned additions. The wall does remind me of the walls around the Old City, built by an Islamic nobleman in the sixteenth century. The Old City walls have fortified gates and served defensive purposes. To be charitable to the Israelis, the wall serves defensive purposes as well.However, two things strike me about the wall. First, Israel is creating a Palestinian state, albeit one under house arrest. By walling off the West Bank and securing it under military guard, the Israelis are in effect creating a state almost exclusively for the Palestinians. Yet, curiously, Israel continues to build settlements behind the wall, settlements exclusively for Jewish Israelis (when you hear of Jewish settlements in the West Bank, that's what they're talking about). So the wall in this sense serves to regulate Palestinian access to the rest of Israel, while Israelis can cross the wall as they please.

Second, the wall allows Israel to avoid dealing with the issues that created the Israeli government's perceived need for the wall, i.e. Palestinian attacks on Israeli citizens. Whatever those issues are, and Israel's occupation of the West Bank in 1967 certainly ranks high on the list, by creating the wall Israel seeks to remove the possibility of Palestinian attacks without addressing those underlying issues. The creation of a free Palestinian state with open commerce with Israel depends on addressing those issues. The wall represents perhaps the clearest declaration that Israel is not interested in addressing those issues, certainly not in working with the Palestinians in creating a free state.

Now, I'm trying not to take sides on this complex issue: its dynamics are way beyond my bare knowledge of Middle East politics. But whatever the rationales or arguments, I cannot help but feel sympathy for any people placed in a ghetto/put in a gulag/settled on a reservation. The very fact of separating off a people from another shows one party to be way more powerful than the other and such a power disparity cannot help but serve the more powerful party. In short, Israel is getting a lot out of the wall.

Here's an image from Bethlehem. I find a disturbing ambiguity in this graffito. On the one hand, it may be descriptive: look around you, this is freedom in Palestine: restricted commerce, hovering threat of being expelled to the Gaza Strip, high unemployment and restricted access to quality medical care. A free Palestine is actually an ugly reality behind a locked metal door in a concrete wall. On the other hand, and more correctly I think, it may be an imperative: you folks, free us, Palestine. Interestingly, I noticed that most of these graffiti were in English, a language that most Israelis and Palestinians certainly speak fairly well. Yet English is the language we speak, a nation with a vested interest in supporting Israel, even in supporting its building of the wall (I hear about our country pressing Israel not to build more settlements, but I rarely hear about our country protesting the wall itself). In fact, in my more cynical moments I think our own efforts to build a wall between ourselves and Mexico is actually an elaborate ploy to draw criticism away from Israel's wall, at least here at home: if we need to build a wall to safeguard our interest, why should Israel not do the same? So our wall, too, becomes a pawn in international politics. Yet, to be fair, don't countries have the right to safeguard their borders, even to the point of building physical barriers?

Here's an image from Bethlehem. I find a disturbing ambiguity in this graffito. On the one hand, it may be descriptive: look around you, this is freedom in Palestine: restricted commerce, hovering threat of being expelled to the Gaza Strip, high unemployment and restricted access to quality medical care. A free Palestine is actually an ugly reality behind a locked metal door in a concrete wall. On the other hand, and more correctly I think, it may be an imperative: you folks, free us, Palestine. Interestingly, I noticed that most of these graffiti were in English, a language that most Israelis and Palestinians certainly speak fairly well. Yet English is the language we speak, a nation with a vested interest in supporting Israel, even in supporting its building of the wall (I hear about our country pressing Israel not to build more settlements, but I rarely hear about our country protesting the wall itself). In fact, in my more cynical moments I think our own efforts to build a wall between ourselves and Mexico is actually an elaborate ploy to draw criticism away from Israel's wall, at least here at home: if we need to build a wall to safeguard our interest, why should Israel not do the same? So our wall, too, becomes a pawn in international politics. Yet, to be fair, don't countries have the right to safeguard their borders, even to the point of building physical barriers?But that breaks down in the Israeli situation. Let's for the moment grant that Israel has established claim to the Gaza Strip, the Golan Heights and the West Bank. A wall safeguarding those borders would encircle the state. Israel, instead, is walling off Palestinians within its borders. They're walling off not another state, but an ethnic/political group within its borders. That's like our building a wall around the Cherokee nation in North Carolina, then going inside that wall and building additional walls between tribal or kin groups and policing those walls with our military. Again, I cannot help but feel sympathetic to those so walled in.

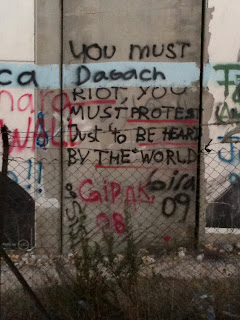

Additionally, here's a strategic image, but from the other side. Again, this one is in English. And again, I find it multivalent. On the one hand, this seems to be a call to the Palestinians to keep rioting and protesting in order to keep their situation in front of the world's eyes. Admittedly, our attention, so stressed these days by so much communication/information/media, seems to have enough energy only to see the most dramatic of issues. Hence, communication becomes wedded to confrontation, to rioting and protest. So Palestinians, according to this graffito, must keep the issue alive through confrontation with the Israelis. On the other hand, being in English the graffito may be addressed to you and me and our country. Perhaps it's a call to those in our country sympathetic to the Palestinian's situation to do our own rioting and protesting against our own country so that our country may hear our own convictions that this wall has serious problems, as does our support for its construction. Again, I'm not personally throwing my own voice behind one side or the other (or the others), since I'm so ill-informed about these issues. Also again, I cannot help but feel sympathy for all those behind this Israeli wall.

Additionally, here's a strategic image, but from the other side. Again, this one is in English. And again, I find it multivalent. On the one hand, this seems to be a call to the Palestinians to keep rioting and protesting in order to keep their situation in front of the world's eyes. Admittedly, our attention, so stressed these days by so much communication/information/media, seems to have enough energy only to see the most dramatic of issues. Hence, communication becomes wedded to confrontation, to rioting and protest. So Palestinians, according to this graffito, must keep the issue alive through confrontation with the Israelis. On the other hand, being in English the graffito may be addressed to you and me and our country. Perhaps it's a call to those in our country sympathetic to the Palestinian's situation to do our own rioting and protesting against our own country so that our country may hear our own convictions that this wall has serious problems, as does our support for its construction. Again, I'm not personally throwing my own voice behind one side or the other (or the others), since I'm so ill-informed about these issues. Also again, I cannot help but feel sympathy for all those behind this Israeli wall.Finally, all the graffiti I saw was inside the wall: the outside was clean. I don't know if this is because the Israeli's do not allow graffiti on the Israeli side or if there's no one really interested in producing it. But I do know this: from the Israeli side, the absence of graffiti makes the wall seem benign, almost a normal part of the buildingscape like all the other concrete buildings of which the Israelis are so fond. The wall without graffiti seems devoid of critical content, full of vagueness, much easier to pass by and not notice, unassuming, modest. Thank you for reading.

Thursday, July 22, 2010

Fences